Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis of Exterior Paints, George Reid House (Block 11, Building 15)

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Research Report Series - 1731

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2012

Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis of Exterior Paints

George Reid House

(Block 11, Building 15)

Williamsburg, Virginia

Table of Contents

| Purpose | 1 |

| Previous Research | 1 |

| Historical Background | 1 |

| Sampling Procedures | 3 |

| Sampling Locations | 3 |

| Results of Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis | 5 |

| South Door Leaf | 7 |

| Shutters | 9 |

| Cornice Fragment | 11 |

| North Door Architrave | 13 |

| West Gable Window | 15 |

| First-Floor Windows | 16 |

| South Door Architrave | 17 |

| South Cornice and Soffit | 18 |

| South Weatherboards | 19 |

| Results of Binding Media Analysis with Fluorochrome Stains | 20 |

| Results of Pigment Identification with Polarized Light Microscopy | 30 |

| Results of Colorimetry | 33 |

| Conclusion | 35 |

| Appendix | |

| Sampling Memorandum | 36 |

| Procedures | 41 |

| Colorimetry Data | 43 |

| Contact Sheets of Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 45 |

Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis of Exterior Paints

| Structure: | George Reid House, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

|---|---|

| Requested by: | Edward A. Chappell, Director, Architectural Research Dept. |

| Conservator: | Natasha K. Loeblich, Architectural Paint Analyst, Architectural Research Dept. |

| Consultant: | Susan L. Buck, Ph.D., Conservator and Paint Analyst |

| Date: | October 2008 |

Purpose

This examination of finish samples from the exterior of the George Reid House aims to identify the color and composition of the early paints applied to the structure. The finish history over time is also recorded for major elements. This report is part of a larger effort to reexamine exterior finishes on all the eighteenth-century buildings in Williamsburg.

Historical Background

In Eighteenth-Century Houses of Williamsburg, Whiffen states that the current George Reid house was built in the 1780s after an earlier and larger dwelling was taken down.1 This was based on findings from an archaeological dig undertaken at the site in 1963.2 While the foundations of the Reid house (previously called the Barlow House and the Orr House) were rebuilt in the 1920s, the area around the house offered some archaeological information (see figure on the next page).

The evidence for an earlier structure on the approximate site of the Barlow House was provided by the discovery of a robbed foundation trench, 1.58 feet deep below the colonial grade, (or 2.68 feet below modern grade) and extending east-west for a distance of 32'0" on a line 11'8" south of the existing rear wall. The robbed trench had seated a two brick, or 1'6" wall which returned northward at both east and west ends until chopped through by the 1928 foundation trenches. The west return passed partially beneath the west end of the present rear porch, while the east was found under the passage linking the house to the modern kitchen. This easterly trench ran on a line only some 4" west of the east end of the Barlow House suggesting that the latter's east end may have occupied the same position as that of the colonial structure. If this assumption is valid, it can be argued that the north or front walls also occupied the same line, in which case the earlier building would have measured close to 32'0" x 32'0". The thickness of the foundation and the depth to which it was taken suggests that it may have supported a brick building the measurements of which indicate that it would have been a double pile structure..... Dating for the filling of the robbed trench was indicated by the presence of a well-preserved Virginia halfpenny of 1773 which was not issued in the Colony until March of 1775. Fragments of a creamware cup were also retrieved from the bottom of the trench and this could not have found its way there until 1770 or later.32

The presence of the 1773 halfpenny in the trench indicates that the earlier structure was not torn down until 1775 at the earliest. The earlier building may have been built around 1737 while the land was owned by Edward Barradall. Captain Hugh Orr, a blacksmith bought the property with its existing forge in 1743 and lived there until his death in 1763 or 1764. Catherine Orr, his widow apparently occupied the house until 1788, but interestingly, Humphrey Harewood notes in his register in 1782 that George Reid was paying for repairs to a structure on the lot.4 Reid officially bought the property in 1789 and died in 1792. It is therefore presumed that the current house was built around 1789-90 immediately after Reid purchased the property. It is possible that some of the elements from the George Reid House were reused from the earlier structure, particularly easily removed elements. Reid's window stayed on in the house until 1814.

The George Reid house was restored by Colonial Williamsburg in 1930-31, as detailed in an undated restoration report.5 Though the house appears much the same as it does today in period photographs (see below), the restoration report notes that this building was in poor condition and that it was necessary to replace many of the elements. The replacements were based on surviving elements on the house or local precedent. The large scale replacement of original elements makes paint analysis more difficult and problematic at this site.

Figure from 1970 Archaeological Report on the George Reid House site showing earlier foundations

Figure from 1970 Archaeological Report on the George Reid House site showing earlier foundations

Sampling Procedures

Thirty samples were taken from the exterior of the house on July 25, 2008 by Chappell and Loeblich. Both returned on August 8, 2008 to take two more samples from the gable window on the west elevation. This required a tall ladder which was kindly provided by the Paint Shop. Additionally, one sample was taken on August 7, 2008 and one on October 21, 2008 by Loeblich from a section of exterior cornice bed molding (GRH 003-07) that is held in the Colonial Williamsburg Architectural Fragments Collection.

| Sample # | Location |

|---|---|

| GR1 | South door leaf, exterior face, west (left) middle panel, top ovolo ½" east of west end |

| GR2 | South door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end |

| GR3 | South door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, top bevel ½" east of west end |

| GR4 | South door leaf, exterior face, east (right) bottom panel, top bevel ½" east of west end |

| GR5 | South door frame, head, soffit, middle, 1¼" east of west end |

| GR6 | South door frame, east (right) architrave, backband, face of cyma, 7" above bottom |

| GR7 | South door frame, west (left) architrave, outer edge, ½" below tenth weatherboard, counting from bottom |

| GR8 | South door frame, west (left) architrave face, in groove of bead, 1' 4" above sill |

| GR9 | South door frame, west (left) architrave, outer edge ¼" below eighth weatherboard |

| GR10 | South exterior cornice, bed mold, bottom of fillet above bottom cyma 10" east (right) of west (left) window |

| 4 | |

| GR11 | South exterior cornice, bed mold, face of fillet above bottom cyma immediately above east (right) jamb of east window (and of west wall of hyphen) |

| GR12 | South wall, 1930-31 weatherboard, immediately below ninth weatherboard, 1" east of northeast porch post |

| GR13 | [Not used] |

| GR14 | South wall, shutter on east first-floor window, outer shutter (of two hinged together), flat rear face of bottom panel, lower west (left) corner near H hinge |

| GR15 | South wall, shutter on east window, inner shutter, rear face of left stile 5" above bottom rail, ¾" west of panel, near HL hinge |

| GR16 | South wall, east window frame, west exterior facing, 1" east of outer edge 1' 2" above base |

| GR17 | South wall, east window, inner shutter, flat rear of bottom panel 1" out from bottom west corner |

| GR18 | South wall, east window, inner shutter, paint pulled loose from red-embedded pine, west (left) stile, immediately adjoining third rail, counting from bottom |

| GR19 | South wall, east window, outer shutter, outer (raised panel) face, top ovolo on bottom panel adjoining second rail, 1½" west of east rail, adjoining ghost of a latch plate |

| GR20 | South wall, east window, outer shutter, second stile, counting from bottom, 2" above bottom and 1½" west of east stile |

| GR21 | South wall, west window, east shutter, paneled outer face, bottom bevel of bottom panel, 1" west of east end, adjoining raised field |

| GR22 | South wall, west window, east shutter, outer face, top rail, ovolo ½" west of east end, adjoining flat face |

| GR23 | South wall, west window, east shutter, outer face, top panel, east (right) bevel adjoining bottom bevel and raised field |

| GR24 | South wall, west window, east shutter, west (left/hinge) stile, east edge adjoining lower west corner of top panel |

| GR25 | South exterior cornice, bed mold, face of fillet above bottom cyma 1' east (right) of east window |

| GR26 | South wall, soffit of eaves, sheathing, 10" out from bed mold and 8" east of west window jamb in east window |

| GR27 | North wall, east window, east shutter, outer (raised panel) face, second panel, upper east corner, bevel at the intersection of ovolos |

| GR28 | North wall, west window, west shutter, outer face, bottom panel, upper bevel, west end 1" from upper west intersection of ovolos |

| GR29 | North wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 3" above bottom, ½" in from backband |

| GR30 | North wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, outer edge in joint between backband and principal piece, 2' 6" above bottom |

| GR31 | North wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 2' 2" above bottom and at inner edge of the backband |

| GR32 | Exterior cornice bed molding fragment (GRH 003-07), 4½" from right side, bottom of cymatium |

| GR33 | West wall gable, small early window south of chimney stack, north jamb at intersection with head |

| GR34 | West wall gable, small early window south of chimney stack, south jamb at intersection with head |

| GR35 | Exterior cornice bed molding fragment (GRH 003-07), 3½" from right side, in recess above cymatium |

Results of Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis

The majority of the samples collected from the exterior of the George Reid house have incomplete early stratigraphies. The lack of early paint data is either due to replacement of original material during the extensive restoration of the house in the 1930s or scraping away of the early paint during repainting. Since the early data is so fragmentary it is difficult to be certain of the exact stratigraphy and the way in which the paint histories of certain elements line up.

The few elements that were discovered to have retained early paint include the south door leaf, the north door architrave, the west gable window, shutters on the east window of the south elevation, and an exterior cornice section from the Architectural Fragments Collection. Almost all of these elements begin with remnants of a red-brown paint that appears to be the earliest finish. (The only exception was the west gable window which has a very weathered surface and is missing all the early layers before generation 5). The red-brown paint appears to have been a presentation surface and not just a primer. There are no obvious dirt accumulations above it, but the red-brown paint is so worn and fragmentary in most samples that it must have been exposed to the elements for some time. The red-brown paint was found on doors, trim, and shutters so it seems possible that the house was first painted a monochromatic red-brown. If the house does indeed date to around 1790 this would seem to be a late use of red-brown paint, since around this period many buildings were beginning to be painted in white.

The next generation of paint was a dull yellow in color and was only found on the shutters and the south door. The dull yellow paint was pigmented with lead white, yellow ochre, and chalk and seems to have had an oil binder. There was no evidence of this paint on the cornice fragment and north door architrave.

Generation 3 was a cream-colored paint that was found on the shutters, the cornice fragment, and the north door architrave. Generation 4 was a thickly-applied red-brown paint that was found on the south door leaf, the shutters, and the cornice fragment. This layer was slightly lighter in color than the generation 1 red-brown paint. The shutters, the cornice fragment, the north door architrave, and the gable window were all painted cream in generation 5 so the house may have had a monochromatic color scheme in this period. The evidence for generation 6 was very limited. One shutter sample had a black paint applied in this generation. The cream-colored paint below it was cracked with age before the black paint was applied. This shutter sample was taken from inside the beveled frame of a recessed panel so it may represent a decorative scheme in which certain details were highlighted. In about the same period there was evidence of a resinous tan paint on some of the south door leaf samples. In generation 7 there was evidence that a cream-colored paint was applied to the shutters, the cornice fragment, the north door architrave, and the gable window. Generation 8 was only found on the cornice fragment and the north door architrave. This white paint was the first layer to contain the pigment zinc white which dates this layer to after 1845.6 After this the samples have more complete stratigraphies and different elements are painted in different colors. The shutters were generally painted in shades of green, the south door in shades of dark brown, and the north door architrave and windows in shades of white and cream, while the south door architrave, cornice, weatherboard, and soffit were painted gray. This suggests that for the latter part of its life, the structure has been painted gray with white trim, brown doors, and green shutters similar to the color scheme that exists now. The gable window used to be painted white like the other windows, but in the last repainting was painted gray to match the weatherboards.

6The table below gives the stratigraphy for various elements. Dashes represent layers that are not present in a sample while question marks represent where samples fractured or were disrupted and there is missing information.

| South Door Leaf | Shutters | Cornice fragment | North door architrave | Gable window | Windows | South cornice, weatherboards, soffit, door architrave | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15-22 | modern dark brown | modern dark green | ? | modern white | modern white | modern white | modern gray |

| 14 | dark brown | gray primer, dark green | ? | cream | cream | cream | gray |

| 13 | dark brown | dark green | ? | cream | cream | cream | gray |

| 12 | dark brown | dark green | ? | white | white | white | gray |

| 11 | light green | light green | ? | white | white | white | gray |

| 10 | cream | gray primer, dark green | ? | cream | - | cream | cream |

| 9 | ? | gray primer, dark green | ? | cream | - | ? | ? |

| 8 | ? | - | white | white | - | ? | ? |

| 7 | ? | cream | cream | cream | cream | ? | ? |

| 6 | tan | black | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| 5 | - | cream | cream | cream | cream | ? | ? |

| 4 | red-brown | red-brown | red-brown | - | - | ? | ? |

| 3 | - | cream | cream | cream | cream | ? | ? |

| 2 | dull yellow | dull yellow | - | - | ? | ? | ? |

| 1 | red-brown | red-brown | red-brown | red-brown | ? | ? | ? |

| resinous sealant | resinous sealant | resinous sealant | resinous sealant | ? | ? | ? |

South Door Leaf

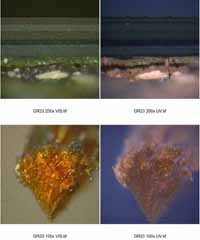

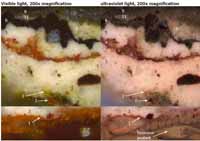

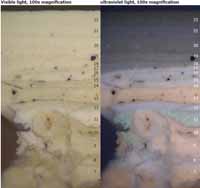

Four samples (GR1-4) were taken from the south door and all of them have some evidence of the earliest paint layers. There are pockets of resinous sealant trapped in the wood cells. The dull-orange fluorescence color of this resin in reflected ultraviolet light is characteristic of shellac, but further analysis would be needed to identify the resin. Above the sealant are remains of the generation 1 red-brown paint. This paint must have been left on the surface for a long period of time, as it is extremely worn in all samples. The resinous sealant and remains of the generation 1 red-brown paint can be seen in the lower crosssection image (sample GR4) on this page. This stratigraphy of this sample is disrupted and is missing many early layers.

The upper cross-section image on this page (sample GR2) has the generation 2 dull yellow paint, which has a few yellow pigment particles. This paint is found on the south door leaf and shutters, while the cornice fragment and north door architrave seem to have been painted cream in the same period. The dull yellow paint contains lead white, yellow ochre, and chalk while the cream-colored paint contains lead white and chalk. Generation 3, a cream-colored paint that was found on the shutters and north door architrave, is missing from the door samples so this element may have remained dull yellow in this period. Generation 4 was a thick red-brown paint that is also found on the south door leaf, shutters, and the cornice. This paint was more pink in color than the generation 1 paint and has clumps of white pigments.

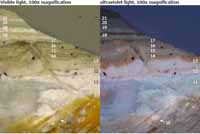

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end

Sample GR4, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) bottom panel, top bevel ½" east of west end

Sample GR4, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) bottom panel, top bevel ½" east of west end

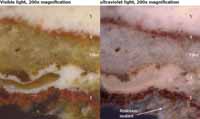

The cross-section image below from sample GR2 shows the more recent paint layers that were applied to the south door leaf. Above the red-brown paint of generation 4 was a resinous tan paint that may have been applied in generation 6 and corresponds to the black paint found in one shutter sample in this period. After this the stratigraphy of all the south door samples skips to generation 10, a cream-colored paint. The generation 10 cream-colored paint was the first generation on many elements on the southern elevation, including the cornice, the weatherboards, the soffit below the second-floor, and the rear door architrave. It seems likely that this may represent the 1930s restoration of the house when many elements were replaced. Generation 11 was a light green paint that is also found on the shutters. After this the south door was consistently painted in shades of dark brown.

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end

Shutters

Only the two shutters on the east window on the south elevation had early paint evidence. These shutters have an unusual one-sided configuration that may have been hard to replace. Additionally, the south kitchen addition could have sheltered this window from wear. Most of the other shutters seem to have been replaced or have lost their early finish history through weathering. Interestingly, the pre-restoration image of the house on page 3 seems to show that the north elevation shutters have been replaced with louvered shutters and the east elevation shutters are already missing.

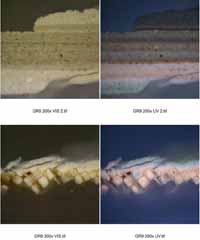

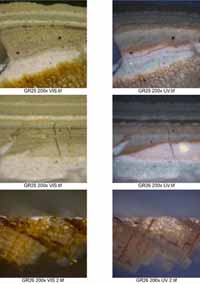

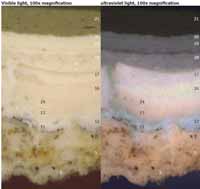

The cross-sections images below (sample GR19) are from one of the shutters on the east window of the south elevation. As seen on the south door leaf, generation 1 was a red-brown paint and generation 2 was a dull yellow paint that is quite fragmentary in this sample. Generation 3 was cream-colored paint also found on the north door architrave. Generation 4 was a red-brown paint that was also found on the south door and cornice fragment. Generation 5 was a cream-colored paint. Evidence of generation 6 was only found on this one shutter and it was a black paint. Around the same time, the south door leaf seems to have been painted tan. Generation 7 was a cream-colored paint and generation 8 was missing from all the shutter samples. Generations 9 and 10 are green finish paints with almost no fluorescence in reflected ultraviolet light, above coarse gray primers. The dark fluorescence suggests the green paints may contain a copper-based pigment like verdigris since these tend to quench fluorescence. Generation 11 was a light green paint also found on the south door leaf.

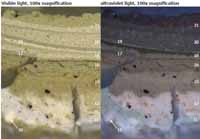

Sample GR19, south wall, east window, outer shutter, outer (raised panel) face, top ovolo on bottom panel adjoining second rail, 1½" west of east rail, adjoining ghost of a latch plate

Sample GR19, south wall, east window, outer shutter, outer (raised panel) face, top ovolo on bottom panel adjoining second rail, 1½" west of east rail, adjoining ghost of a latch plate

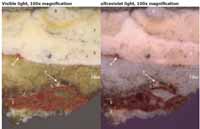

The cross-section image below is from another shutter on the same window (sample GR18) and retains more of the upper layers. This sample skips from the yellow-pigmented paint in generation 2 to the cream-colored paint of generation 7. The cream-colored paint had some mold growth seen below as brown clumps. The gray primers and green finish coats of generations 9 and 10 can be seen in this cross-section. Generation 11 and above were all varying shades of green paint that seem to have gotten darker over time. Some of the later layers also had gray primers.

Sample GR18, south wall, east window, inner shutter, paint pulled loose from red-embedded pine, west (left) stile, immediately adjoining third rail, counting from bottom

Sample GR18, south wall, east window, inner shutter, paint pulled loose from red-embedded pine, west (left) stile, immediately adjoining third rail, counting from bottom

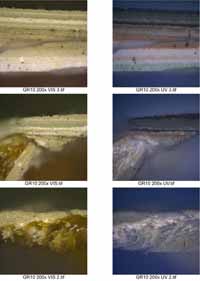

Cornice Fragment

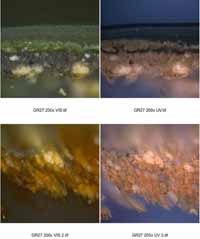

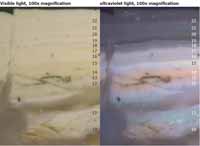

A section of molding is held in the Architectural Fragments Collection and was probably collected around the time of the 1930s restoration. The fragment appears to match the cornice on the south elevation, but both are of a common form. The old label on the reverse says the piece is a fragment of a bed molding from the main cornice of the Barlow (or Orr) House which is the old name for the Reid House. The molding is quite weathered and some of the paint seems to have been applied after the piece was worn down. There is red paint visible on the surface, but it seems to be confined to the cymatium. The molding section had evidence of early finishes, while all the samples taken from the present cornice did not. Sample GR32 from the fragment began with a red-brown paint that was thicker than that found on other samples in the same generation. The sample is disrupted above the generation 1 red-brown paint and evidence of the generation 2 dull yellow paint may have worn away. Generation 3 was a creamcolored paint that was also found on the north door architrave. After this the paint was disrupted by the application of some sort of yellowish putty or filler. This material has a bluish fluorescence in reflected ultraviolet light and appears somewhat translucent in reflected visible light. It does not appear to be either a limewash or an oil paint, but may have been applied to fill cracks, level the surface, or for even for waterproofing. Generation 4 was a red-brown paint also found on the south door leaf and shutters, although it is quite thin in this sample.

Sample GR32, exterior cornice bed molding fragment (GRH 003-07), 4½" from right side, bottom of cymatium

Sample GR32, exterior cornice bed molding fragment (GRH 003-07), 4½" from right side, bottom of cymatium

The photomicrographs below are from the same sample and show the more recent layers applied to the cornice fragment. At the bottom of the cross-section are portions of the generation 3 cream-colored paint that flowed down a crack and under the generation 1 red-brown paint. The most recnet layers are worn suggesting that the paint was allowed to wear almost away. Generation 5 and 7 were cream-colored paints also found on many of the other early elements. There was no evidence of the black and tan paints applied to the shutters and doors in generation 6. Generation 8 was a white paint that is the first layer to contain zinc white, dating it to after 1845. There are no more layers after generation 8, but the fragment is quite weathered so later layers may have worn off. The weathered surface of this element may be indicative of the extreme wear on the surface that existed on elements before the 1930s restoration. This may explain why it was felt necessary to replace so many of the elements at that time.

Sample GR32, exterior cornice bed molding fragment (GRH 003-07), 4½" from right side, bottom of cymatium

Sample GR32, exterior cornice bed molding fragment (GRH 003-07), 4½" from right side, bottom of cymatium

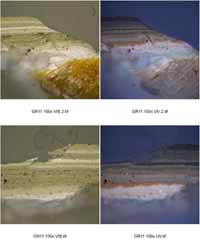

North Door Architrave

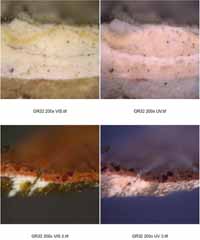

The architrave of the north elevation front door had one of the most complete stratigraphies of all the elements on the house. Along with the south door leaf and the shutters, the architrave sample began with remnants of the generation 1 red-brown paint. At some point the house was allowed to weather so significantly that only the red-brown paint that was absorbed into wood cells survived. In the wood cells pockets of a resinous sealant also survived that have a muted orange fluorescence characteristic of aged shellac. There is no evidence of the generation 2 dull yellow paint. In generation 3 a cream-colored paint was applied that was also found on the cornice fragment. The generation 4 red-brown paint and the generation 6 black and tan paints were not found on the door architrave, instead it was painted cream or white throughout its history.

Sample GR29, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 3" above bottom, ½" in from backband

Sample GR29, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 3" above bottom, ½" in from backband

Generation 8 on the front door architrave was a white paint that is also found on the cornice fragment. Generations 9 through 22 were white and cream-colored paints that appear to have a variety of binders and pigments. After the initial red-brown paint was applied in generation 1, the architrave was always painted white or cream.

Sample GR30, north wall, exterior door, west architrave, outer edge in joint between backband and principal piece, 2' 6" above bottom

Sample GR30, north wall, exterior door, west architrave, outer edge in joint between backband and principal piece, 2' 6" above bottom

West Gable Window

The gable window on the west elevation was the only window that appeared to have early paint evidence when examined on site. Cross-sections from this window (sample GR30) began with three jumbled cream-colored paints that probably correspond to generations 3, 5 and 7 on the north door architrave. In fact, the gable window seems to have been painted to match the north door architrave in all but the most recent paint generation. When the house was last repainted the gable window was painted to match the surrounding weatherboards instead of white like the other windows. The earliest paint layers are missing from the west gable window, but this is probably due to weathering and the surface of the window is quite worn.

Sample GR30, north wall, exterior door, west architrave, outer edge in joint between backband and principal piece, 2' 6" above bottom

Sample GR30, north wall, exterior door, west architrave, outer edge in joint between backband and principal piece, 2' 6" above bottom

First-floor Windows

Only one sample was taken from one of the first-floor windows because on-site investigation suggested the sash and frames were either replaced or too worn to have early paint evidence. This is evidenced by the cross-section image below from sample GR16 that begins with generation 10, a cream-colored paint. Many elements begin with this same finish layer suggesting that this generation represents the 1930s restoration of the house. The restoration report notes that many elements were replaced at this time. The cross-section indicates that the windows have always been painted white or cream since they were installed.

Sample GR16, south wall, east window frame, west exterior facing, 1" east of outer edge 1' 2" above base

Sample GR16, south wall, east window frame, west exterior facing, 1" east of outer edge 1' 2" above base

South Door Architrave

Like the first-floor windows, the south door architrave began with the cream-colored paint of generation 10 as shown in the cross-section images below from sample GR5. This suggests that the south door architrave also dates to the period of the 1930s restoration. Since its installation, the complete evidence suggests that the south door architrave has always been painted to match the north door architrave in shades of white and cream.

Sample GR5, south door frame, head, soffit, middle, 1¼" east of west end

Sample GR5, south door frame, head, soffit, middle, 1¼" east of west end

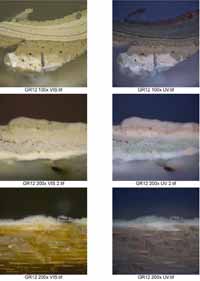

South Cornice and Soffit

The cornice and weatherboards on the southern elevation have an identical stratigraphy. They also began with a cream-colored paint that is generation 10 on other elements. It seems likely that the cornice and weatherboards were replaced in the 1930s restoration of the house. Generation 11 was a light gray paint, but generations 12 through 20 were all gray paints that were similar in color to the current paint on the house, generation 21.

Sample GR11, south exterior cornice, bed mold, face of fillet above bottom cyma immediately above east (right) jamb of east window (and of west wall of hyphen)

Sample GR11, south exterior cornice, bed mold, face of fillet above bottom cyma immediately above east (right) jamb of east window (and of west wall of hyphen)

South Weatherboards

Like many other elements on the southern elevation, the weatherboards also began with a cream-colored paint in generation 10, as shown in the cross-section images below from sample GR12. Thus, they are likely to have been added in the 1930s restoration. The weatherboards share an identical stratigraphy with the cornice, soffit, and door architrave on the southern elevation.

Sample GR12, south wall, weatherboard immediately below ninth weatherboard, 1" east of northeast porch post

Sample GR12, south wall, weatherboard immediately below ninth weatherboard, 1" east of northeast porch post

Results of Binding Media Analysis with Fluorochrome Stains

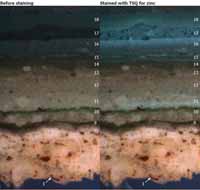

Several cross-sections with early paint layers were chosen for binding media analysis. The cross-sections were treated with biological fluorochrome stains that mark out proteins, carbohydrates, oils, and zinc (Zn2+) in the individual layers.

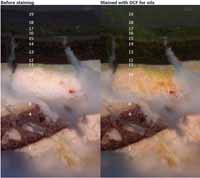

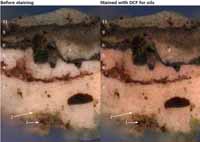

The first-generation red-brown paint in sample GR2 seemed to react positively for oils when the fluorochrome stain DCF was applied. This stain marks out aged oils (saturated lipids) with a pink positive reaction color and less aged oils (unsaturated lipids) with a yellow reaction color. In the photomicrographs below, the remnants of the generation 1 red-brown paint have become slightly more pink after staining. Since the layer was already red in ultraviolet light, it may be masking the pink positive reaction color. Further analysis will be need to confirm that this paint has an oil binder, but it seems likely.

The generation 2 dull yellow paint developed a pink color after staining with DCF that indicates strong positive reaction for aged oils. Thus, this was also probably an oil paint.

Generation 3 was missing from this sample, but the thick red-brown paint in generation 4 seemed to become more yellow indicating a positive reaction for less aged oils. Again, the red autofluorescence color of the paint may be masking a reaction for aged oils.

All three early layers appear to be typical eighteenth century and early nineteenth century paints with oil binders.

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

The photomicrographs below show the results of staining with DCF for oils on more recent layers. As seen on the previous page, there was a slight positive reaction in the dull yellow paint of generation 2. This layer developed a slight pink reaction color which indicates that saturated lipids (typically found in aged oils) are present. There was a strong reaction in the cream-colored paint of generation 10 with both pink and yellow positive reaction colors appearing, suggesting that saturated and unsaturated lipids are present. The uppermost modern paint layers also showed a strong reaction for unsaturated or uncrosslinked oils with a yellow positive reaction color. These are typically found in comparatively fresher oils. Some of the modern paint layers also had a strong positive yellow reaction color for fresh oils. Many of the other layers could also have oil binders but the oil components could have leached out of the paint through weathering.

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

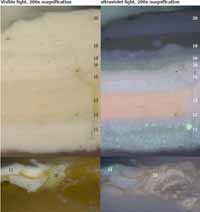

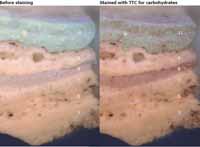

A cross-section from sample GR31 from the north door was also stained with DCF to mark out the presence of oils in the layers. The photomicrographs below show that generations 3 through 9 stained positive for saturated oils with a pink reaction color. Generation 11 had both a pink and yellow reaction color indicating that both saturated and unsaturated lipids are present in this paint which is probably less aged and weathered than the paints below it.

Sample GR31, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 2' 2" above bottom and at inner edge of the backband, ultraviolet light, 100x magnification

Sample GR31, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 2' 2" above bottom and at inner edge of the backband, ultraviolet light, 100x magnification

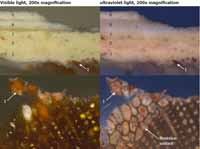

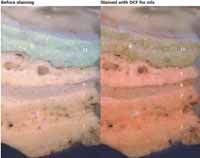

Sample GR19 from a shutter was also tested for the presence of oils with the fluorochrome stain DCF. As seen in the photomicrographs below there were positive reactions in the cream-colored paints of generation 3, generation 5, and generation 7 for aged oils with a pink reaction color. The modern paint that flowed down below the generation 1 paint on the right side of the cross-section showed a strong reaction for comparatively fresh oils with a yellow positive reaction color.

Sample GR19, south wall, east window, outer shutter, outer (raised panel) face, top ovolo on bottom panel adjoining second rail, 1½" west of east rail, adjoining ghost of a latch plate, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

Sample GR19, south wall, east window, outer shutter, outer (raised panel) face, top ovolo on bottom panel adjoining second rail, 1½" west of east rail, adjoining ghost of a latch plate, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

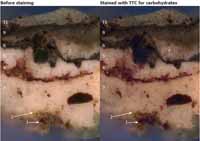

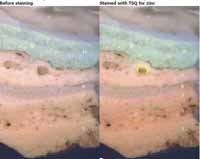

There were no obvious reactions for proteins in any of the early layers, but some of the early layers did react positively for carbohydrates when the stain TTC was applied. Period recipes sometimes call for the addition of a natural plant gum when grinding pigments into an oil binder to aid in dispersion. This may explain the presence of carbohydrates in the early layers. Sample GR19 from a shutter shows that some of the early layers reacted positively for carbohydrates when the stain TTC was applied. This may be due to the addition of a natural plant gum when grinding the pigments into the oil binder to aid in dispersion. The photomicrographs show a dark red positive reaction color in the generation 3 and 5 paints. There are only fragments of the generation 1 red-brown and the generation 2 dull yellow paint in this sample so it is not possible to be sure of the reactions in these layers after staining.

Sample GR19, south wall, east window, outer shutter, outer (raised panel) face, top ovolo on bottom panel adjoining second rail, 1½" west of east rail, adjoining ghost of a latch plate, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

Sample GR19, south wall, east window, outer shutter, outer (raised panel) face, top ovolo on bottom panel adjoining second rail, 1½" west of east rail, adjoining ghost of a latch plate, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

The photomicrographs below from sample GR2 from the south door leaf show that a dark red positive reaction color developed in the generation 2 dull yellow paint as well as in generation 6 and generation 10. There could also have been a positive reaction for carbohydrates in generation 4 but the red autofluorescence color of this layer could be masking the reaction.

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

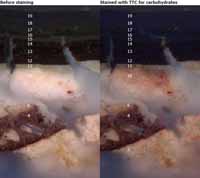

The cross-section image (sample GR31) below is from the north door architrave and shows the early layers on the elements after staining with TTC for carbohydrates. Like the early paint layers on other elements, the early paint layers on the architrave showed faint positive reactions for carbohydrates. The white paint in generation eight stained strongly positive for carbohydrates with a dark red reaction color.

Sample GR31, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 2' 2" above bottom and at inner edge of the backband, ultraviolet light, 100x magnification

Sample GR31, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 2' 2" above bottom and at inner edge of the backband, ultraviolet light, 100x magnification

One sample from the exterior cornice fragment (GR32) was also stained since this had an unusual layer above the generation 4 red-brown paint that appears to be a wood putty or filler. This layer stained weakly positive for carbohydrates with a dark red reaction color when TTC was applied and yellow for less aged oil (unsaturated lipids) when DCF was applied. There was no reaction for protein in the layer. Further analysis will be needed to characterize the layer, but the fluorochrome staining suggests it contains an oil and a starch, so is probably not a glue-based filler.

Sample GR32, exterior cornice bed molding fragment (GRH 003-07), 4½" from right side, bottom of cymatium, ultraviolet light, 100x magnification

Sample GR32, exterior cornice bed molding fragment (GRH 003-07), 4½" from right side, bottom of cymatium, ultraviolet light, 100x magnification

The fluorochrome stain TSQ marks out the presence of zinc (Zn2+) with a bright blue reaction color. In the photomicrograph below from a shutter sample, the first layer to show a positive reaction for zinc was the light green paint of generation 11. The zinc is most likely present in the form of zinc white pigment which was not available for use in oil paint until after 1845.

Sample GR18, south wall, east window, inner shutter, paint pulled loose from red-embedded pine, west (left) stile, immediately adjoining third rail, counting from bottom, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

Sample GR18, south wall, east window, inner shutter, paint pulled loose from red-embedded pine, west (left) stile, immediately adjoining third rail, counting from bottom, ultraviolet light, 200x magnification

On the north door architrave, generation 8 was the first layer to react positively when the stain TSQ was applied to mark out the presence of zinc (Zn2+). This layer had a faint positive reaction with spots of bright blue appearing in the paint after staining. Generation 11 also stained positive for zinc. The zinc is most likely present as zinc white pigment which was not available for use in oil paint before 1845.

Sample GR31, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 2' 2" above bottom and at inner edge of the backband, ultraviolet light, 100x magnification

Sample GR31, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 2' 2" above bottom and at inner edge of the backband, ultraviolet light, 100x magnification

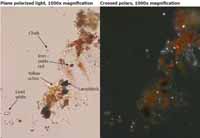

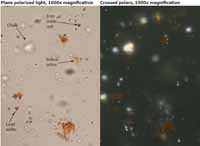

Results of Pigment Identification with Polarized Light Microscopy

Dispersed pigments from the first-generation red-brown paint, and the second-generation dull yellow and cream-colored paints were examined with polarized light microscopy to determine the pigment composition. The first generation red-brown paint was found to contain an iron oxide red pigment (possibly red ochre or Spanish brown) and calcium carbonate (chalk is a common paint extender). These pigments were present in a range of sizes suggesting a hand-ground paint. A few particles of yellow ochre, charcoal black, and lead white were also detected. Because of the thinness of the red-brown paint it was difficult to isolate for sampling, so it not possible to be sure that the other pigments are not contaminants from other paint layers. In cross-section there were no yellow, black, or white pigment clumps visible in the red-brown paint, so if these other colored pigments are present, they are in low concentration. All of the pigments detected in the red-brown paint are common and relatively inexpensive pigments that were eadily available in the eighteenth century.

Sample GR15, south wall, shutter on east window, inner shutter, rear face of left stile 5" above bottom rail, ¾" west of panel, near HL hinge, dispersed pigment sample

Sample GR15, south wall, shutter on east window, inner shutter, rear face of left stile 5" above bottom rail, ¾" west of panel, near HL hinge, dispersed pigment sample

The second-generation dull yellow paint on the door leaf was found to contain yellow ochre, chalk and lead white. Some red pigment particles were also detected that could be contaminants from the redbrown paint since it was difficult to isolate the early layers for sampling. In cross-section it is possible to see large yellow-brown pigment clumps that may be the yellow-brown mineral geothite but attempts to isolate these for analysis were unsuccessful. As with the red-brown paint, all of the pigments detected in the red-brown paint are common and relatively inexpensive pigments that were readily available in the eighteenth century.

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end, dispersed pigment sample

Sample GR2, south door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end, dispersed pigment sample

Only lead white and chalk were detected in the third-generation cream-colored paint on the north door architrave. The large pigment size and the pigment composition is consistent with an eighteenth-century paint.

Sample GR29, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 3" above bottom, ½" in from backband

Sample GR29, north wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 3" above bottom, ½" in from backband

Results of Colorimetry

Color measurements were undertaken for this report on a samples with the generation 1 red-brown paint (GR32), three samples with the generation 2 dull yellow paint (GR21, GR27, and GR29), and one sample with the generation 2 cream-colored paint (GR30).

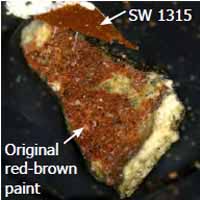

Sample GR32 from the cornice fragment was chosen for analysis because it had a portion with a large area of the generation 1 red-brown paint. This paint had an L* value of 38.57, an a* value of +13.57, and a b* value of +11.59 in the CIE L*A*b* color system. In the Munsell color system this paint has a hue of 9.7R, a value of 3.4, and a chroma of 2.8. Under magnification with a color-corrected light source, the best commercial paint match found to the first-generation red-brown paint was a swatch of Sherwin Williams 1315 "Chutney Brown" which has an L* value of 34.91, an a* value of +13.69, and a b* value of +12.95. This commercial paint swatch is different from the color of the first-generation red-brown paint by a ΔE value of 3.91. This commercial paint swatch is a good match for the original paint since it is very close in color, but is slightly darker than the original paint. Thus, this swatch represents a paint color that is a good match for the red-brown paint which appears to have been applied to all the elements in generation 1.

Best commercial paint match to generation 1 red-brown paint, Sherwin Williams 1315

Best commercial paint match to generation 1 red-brown paint, Sherwin Williams 1315

Upside down uncast sample GR32 with generation 1 red-brown paint and color match

Upside down uncast sample GR32 with generation 1 red-brown paint and color match

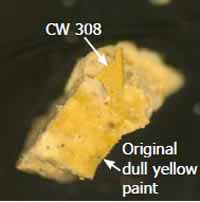

After all the generation 2 dull yellow paint samples were measured, the closest match to the average was from sample GR27 and had an L* value of 69.13, an a* value of +1.02, and a b* value of +25.71. In the Munsell color system this paint has a hue of 1.3Y, a value of 6.4, and a chroma of 3.5. Like the red-brown paint, the dull yellow paint is quite variable in color and this measurement was different from the average by a ? value of 2.45. The high ? value can be explained by the variability of the paint caused by hand grinding the pigments into the binder. Under magnification with a color-corrected light source, the best commercial paint match was a swatch from the Williamsburg Color Collection CW 308 "Scrivener Store Gold" which has an L* value of 68.18, an a* value of +0.80, and a b* value of +29.19. This commercial paint swatch is different from the color of the second-generation dull-yellow paint by a .E value of 3.61. The commercial paint swatch represents a paint color that is a good match for the dull yellow paint that was applied to the doors and shutters elements in generation 2.

Best commercial paint match to generation 2 dull yellow paint, Williamsburg Color Collection CW 308

Best commercial paint match to generation 2 dull yellow paint, Williamsburg Color Collection CW 308

Upside down uncast sample GR29 with generation 2 dull yellow paint and color match

Upside down uncast sample GR29 with generation 2 dull yellow paint and color match

The cream-colored paint that was applied to the shutters, cornice, gable window, and door architrave in generation 3 was found to contain only lead white and chalk. This paint had an L* value of 76.63, an a* value of -0.40, and a b* value of +12.74. In the Munsell color system this paint has a hue of 3.4Y, a value of 7.8, and a chroma of 1.6. The best match to this is Sherwin Williams 6149 "Relaxed Khaki". This paint has an L* value of 76.97, an a* value of -0.94, and a b* value of +13.15, which is different from the original paint by a low ? value of only 0.76.

Best commercial paint match to generation 2 cream-colored paint, Sherwin Williams 6149

Best commercial paint match to generation 2 cream-colored paint, Sherwin Williams 6149

Upside down uncast sample GR27 with generation 3 cream-colored paint and color match

Upside down uncast sample GR27 with generation 3 cream-colored paint and color match

The above color is quite dark due to the darkening and yellowing of the oil binder with age and weathering. Since this paint is pigmented only with lead white and chalk, the current color is probably not indicative of its original appearance. Therefore, it would be more appropriate to repaint with a paint that is matched to a batch of fresh lead white in oil, as this is closer to the original intent. A good commercial paint match to a sample board of fresh lead white and linseed oil is Martin Senour CW 707 "Bracken Cream Medium White" from the Williamsburg Color Collection. This paint has an L* value of 90.40, an a* value of -1.60, and a b* value of +10.60, which is different from a sample batch of fresh lead white in linseed oil paint by a low ? value of only 1.02. Hence, this commercial paint match could be used for reproducing the cream-colored paint used on the cornice and north door architrave in generation 2.

Best commercial match to fresh lead white in linseed oil, Martin Senour CW 707

Best commercial match to fresh lead white in linseed oil, Martin Senour CW 707

Conclusion

Only a few elements on the George Reid House were found to retain evidence of the early paint history of the house. The lack of data is probably due to the restoration of the house in the 1930s when many elements were replaced. The few elements that were discovered to have retained early paint include the south door leaf, the north door architrave, the west gable window, shutters on the east window of the south elevation, and an exterior cornice section from the Architectural Fragments Collection. All of these elements (except the gable window which has a disrupted early surface) begin with a red-brown paint applied over a resinous sealant. (See page 6 for a table with the finish history of all the elements sampled.) The fact that the red-brown paint was found on a variety of elements suggests that it was applied monochromatically to the house. This paint cannot be a primer because the layer is so worn and fragmentary that it must have been exposed to weathering as a presentation surface for some time. The paint is dark in ultraviolet light suggesting that it has an oil binder. Fluorochrome staining of the binding medium, however, was inconclusive because the red autofluorescence of the layer may be masking a positive reaction for oils. The red-brown paint was found to contain an iron oxide red, lead white, and chalk. Some yellow ochre was also detected but is likely a contaminant from the layer above.

Archaeological findings suggest that there was a larger brick structure on the same site as the Reid house that could not have been demolished before 1775. The previous owner died in 1763 or 64 and his widow occupied the property until Reid purchased it in 1789. Therefore, the Reid house was likely built after 1789. Considering this comparatively late date, when the house is next repainted, it should probably be repainted monochromatically in a red-brown paint. This would be the closest to its appearance in the 1774-1781 period of interpretation in the historic area. Choosing the generation 1 red-brown paint finish is also desirable because the information about that paint generation is more clear than with some later generations. This would seem to be a late use of red-brown paint in Williamsburg, since by this time most structures had been repainted in a more classical white or cream. It is possible that some of the elements of the George Reid House were reused from the earlier structure and this might explain the red-brown paint, but more structural research would be needed to clearly identify elements that were reused.

On the south door leaf and the shutters on the east window of the south elevation, generation 2 was a dull yellow paint. This paint was colored with yellow ochre, lead white, and chalk. A few iron oxide red particles were also detected but these are likely to be contaminants from the generation 1 paint. This layer did react positively for aged oils when fluorochrome stains were applied, suggesting that it has an oil binder. The layer also reacted positively for carbohydrates, which may indicate the addition of a natural gum to aid in pigment dispersion when grinding. The other early elements were missing evidence of this layer so either the paint was lost to wear or the cornice and door architrave remained red-brown in this period. A commercial color match is provided that could be used for reproducing this color when the house is next repainted. However, the comparatively late date of this house means that the dull yellow paint was probably not applied until the nineteenth century.

In generation 3 and 5 a cream-colored paint was applied to the shutters, cornice fragment, west gable window, and north door architrave. This paint appears to have an aged oil binder and was colored with lead white and chalk. These layers were not found on the south door, so either these layers wore away on this element or it was not repainted in either generation. A commercial color match for this creamcolored paint is also provided. Surprisingly, in generation 4 a second red-brown paint was applied to the south door, the shutters, and the cornice fragment. The north door architrave and gable window were missing this layer so it was either worn off or these elements remained cream in this period. There is only fragmentary evidence for generation 6. A tan paint was applied to the south door leaf in this period 36 and one of the shutters appears to have been painted black. The black paint flows into cracks in the paint below indicating that it was not applied at the same time as the generation 5 cream-colored paint. None of the other elements seem to have been repainted in this period. In generation 7 everything but the door was painted a monochromatic cream with a paint that appears to be composed of lead white in oil. (The door samples were missing generations 7 through 9, so either layers were lost to wear or the door was not repainted.) Generation 8 was a white paint found on the cornice and north door architrave that stained positive for zinc and therefore probably contains zinc white pigment, dating the layer to after 1845. This means that, at most, the house was repainted on average every eight years. Generation 9 and 10 were also periods when the house was painted a monochromatic white or cream except that in both generations the shutters were painted dark green over a gray primer. A cream-colored paint was applied to the door in generation 10 that matches that applied to the door architrave and windows. This suggests that in generations 7 through 9, which are missing for the door samples, this element may have been painted to match the other trim elements. Generation 10 is the first generation on many elements and it seems likely that this generation corresponds to the 1930s restoration of the house when many elements were replaced with replicas. In generation 11, the windows and north door architrave were painted white, while the south cornice, weatherboards, and south door architrave were painted in a gray paint that is probably close to the current color. The south door and shutters were painted green at the same time. Generations 12-15 continued the same color scheme, but the doors were painted dark brown instead of green.

The surprising amount of evidence on the double shutter on the east window of the south elevation is rare in Williamsburg. Most other early shutters have been lost or have been stripped or dipped removing their finish history. Care should be taken when repairs or repainting are done on this house not to disturb the paint evidence on this important element.

Footnotes

Appendix

Sampling Memorandum

From: Natasha loeblich

Date: July 25, 2008

Re: Reid House Exterior Paint Samples

Block 11, Building 11

This is a list of exterior locations from which we took paint samples today. I have noted our initial observations.

- 1. South door leaf, exterior face, west (left) middle panel, top ovolo ½" east of west end. This is a relatively thin six-panel door with relatively little weathering, but otherwise we see no evidence that this was not originally an exterior leaf in this location. Now dark brown.

- 2. South door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, bottom ovolo 4" west of east end. More or thicker layers than sample 1.

- 3. South door leaf, exterior face, east (right) middle panel, top bevel ½" east of west end.

- 4. South door leaf, exterior face, east (right) bottom panel, top bevel ½" east of west end.

- 5. South door frame, head, soffit, middle, 1¼" east of west end. This has the crispness of 20th-century woodwork, but the architectural reports identify it as original, and you see much paint. Now white.

- 6. South door frame, east (right) architrave, backband, face of cyma, 7" above bottom.

- 7. South door frame, west (left) architrave, outer edge, ½" below tenth weatherboard, counting from bottom. There is a thick buildup of paint here, protected from stripping by the angle of weatherboards.

- 8. South door frame, west (left) architrave face, in groove of bead, 1' 4" above sill.

- 9. South door frame, west (left) architrave, outer edge ¼" below eighth weatherboard. This, like sample 7, is protected by the angle of the weatherboards.

- 10. South exterior cornice, bed mold, bottom of fillet above bottom cyma 10" east (right) of west (left) window. Seems thin, but possibly with old paint on the bottom.

- 38

- 11.South exterior cornice, bed mold, face of fillet above bottom cyma immediately above east (right) jamb of east window (and of west wall of hyphen). You see light gray paint on the bottom, lighter than present light gray. However, there is relatively little wear, and the wood looks very light in color.

- 12. South wall, 1930-31 weatherboard, immediately below ninth weatherboard, 1" east of northeast porch post. This sample taken for comparison. Now painted gray.

- 13. [No sample taken]

- 14.South wall, shutter on east first-floor window, outer shutter (of two hinged together), flat rear face of bottom panel, lower west (left) corner near H hinge. This is an early shutter and appears not to have been stripped or badly weathered. You may see redbrown on the bottom, at the dark southern yellow heart pine.

- 15. South wall, shutter on east window, inner shutter, rear face of left stile 5" above bottom rail, ¾" west of panel, near HL hinge.

- 16.South wall, east window frame, west exterior facing, 1" east of outer edge 1' 2" above base. This looks like 1930-31 finish, and has light-colored wood below many whites.

- 17. South wall, east window, inner shutter, flat rear of bottom panel 1" out from bottom west corner. Again, this looks early.

- 18. Same shutter, paint pulled loose from red-embedded pine, west (left) stile, immediately adjoining third rail, counting from bottom.

- 19. Same window, outer shutter, outer (raised panel) face, top ovolo on bottom panel adjoining second rail, 1½" west of east rail, adjoining ghost of a latch plate. This face of the shutter is much more weathered than the inner one, but it may retain red on the bottom. So a question is whether the dark red is an original layer or simply the earliest modern layer over the weathered shutter.

- 20. Same outer shutter, second stile, counting from bottom, 2" above bottom and 1½" west of east stile. Note that this is taken from an unweathered area that appears to have been protected by a latch plate or other hardware. The inner shutter lacks corresponding ghosts, so the shutters may have been moved among the windows as well as, in this case, joined to avoid the 1930-31 hyphen.

- 21.South wall, west window, east shutter, paneled outer face, bottom bevel of bottom panel, 1" west of east end, adjoining raised field. You see browns here, different from red-brown seen earlier.

- 22. Same shutter, outer face, top rail, ovolo ½" west of east end, adjoining flat face. Wood is light in color, conceivably replaced.

- 23.Same shutter, outer face, top panel, east (right) bevel adjoining bottom bevel and raised field.

- 39

- 24.Same shutter, west (left/hinge) stile, east edge adjoining lower west corner of top panel. Dark, early wood. Note that the outer face of the shutters on this window is less weathered than the rear face, conceivably indicating the shutters were kept closed more here than on the east window, sampled above.

- 25. South exterior cornice, bed mold, face of fillet above bottom cyma 1' east (right) of east window. This is the same element as sample 11 but a separate piece of wood, east of a diagonal joint. Again, the wood is very light, looking c.1930-31.

- 26. South wall, soffit of eaves, sheathing, 10" out from bed mold and 8" east of west window jamb in east window. This surface looks old, but you think it may have the same layers as sample 25, which I think is from c.1930-31.

- 27. North wall, east window, east shutter, outer (raised panel) face, second panel, upper east corner, bevel at the intersection of ovolos.

- 28. North wall, west window, west shutter, outer face, bottom panel, upper bevel, west end 1" from upper west intersection of ovolos. These shutters look early, and the wood is dark s.y.h.p., but we do not see much paint.

- 29. North wall, exterior door, west (right) architrave, middle face 3" above bottom, ½" in from backband. This piece of the door frame looks original and seems to have early layers in spite of having been ruthlessly scraped in the past.

- 30. North wall, exterior door, west architrave, outer edge in joint between backband and principal piece, 2' 6" above bottom

- 31. North wall, exterior door, same piece as sample 29, 2' 2" above bottom and at inner edge of the backband. This appears to be early paint that escaped the scraper. There seems to be cream below light gray.

Note: The beaded frame of the west gable attic window (above collars) is early but requires a long ladder.

E.A.C.

Addendum:

On August 7, 2008, a sample was taken from a cornice section in the Architectural Fragments collection. Two further samples were taken on August 8, 2008 using a tall ladder provided by the painters. Both samples were taken from the attic window in the west gable. This originally has four panes, but the lights have been replaced with a modern grate.

GR32. Exterior cornice fragment (GRH003-07), bottom of cyma, 4½" from right side

GR33. West gable, small early window south of chimney stack, north jamb at intersection with head. You see no early paint surviving in this or 34.

GR34. Same window, south jamb at intersection with head.

Cross-section Preparation Procedures

The samples were initially examined with a stereomicroscope under low power magnification (5 to 50 times magnification) and divided as needed. When possible, a portion of each sample was kept in reserve for future analysis and a portion cast in a labeled cube of a commercial two-part polyester resin manufactured by Excel Technologies, INC. (Enfield, CT). The resin was cured under an incandescent lamp for several hours. The resin cubes were then ground on a motorized grinding wheel with 200 grit sandpaper to reveal the cross-sections. Final finishing was achieved using a Buehler Metaserv 2000 grinder polisher equipped with abrasive cloths from Micro Mesh, INC. with grits of 1500 to 12,000.

Cross-section microscopy analysis was performed using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with an EXFO X-Cite 120 Fluorescence Illumination System fiberoptic halogen light source. The cross-sections were examined at magnifications of 40x, 100x, 200x, and 400x using reflected visible light and a brightfield filter cube. Several fluorescence filter cubes were also used including a UV-2A cube with 330-380nm excitation, a 400nm dichroic mirror, and a 420nm barrier filter, a B-2A cube with a 450-490nm excitation, a 505nm dichroic mirror, and a 520nm barrier filter, and a BV-2A cube with 400-440nm excitation, a 455nm dichroic mirror, and a 470nm barrier filter. The cross-sections were photographed digitally using an integral Spot Flex digital camera with Spot Advanced (v. 4.6) software. The light levels of the images were adjusted in Adobe Photoshop CS2. The color on the digital images is somewhat indicative of the actual color of the paints, but cannot be used for color matching as the printing process can cause color shifts.

Under ultraviolet light many materials have characteristic autofluorescence colors that can suggest their composition. For example, most natural resin varnishes have a bright whitish autofluorescence while oil varnishes tend to be darker in ultraviolet light. Visible light microscopy can also yield valuable information. The presence of soiling layers or weathering can indicate that the finish layer existed as a presentation surface for a period of time. Since many interior finishes, such as faux graining, make use of a predictable sequence of layers, it is important to determine which layers were meant to be final presentation surfaces.

Binding Media Analysis Procedures

To better understand the composition of the paint binders, selected cross-sections were stained with biological fluorochrome stains to indicate the presence of carbohydrates, proteins, oils, and zinc in the paint binders. The stains used were ALEXA (0.1% w/v Alexafluor 488 in dimethylformamide brought to a pH of 9.0 with 0.5% borate) which marks proteins bright green, TTC (4% w/v triphenyl tetrazolium chloride in methanol) which marks carbohydrates dark red-brown, DCF (0.2% w/v 2,7 dichlorofluorescein in ethanol) which marks saturated lipids pink and unsaturated lipids yellow, and TSQ (0.2% w/v N-(6-methyl-8-quinolyl)-p-toluenesulfonamide in ethanol) which marks zinc (Zn2+) blue-white.

Pigment Identification Procedures

Samples with good accumulations of early paints identified through cross-section microscopy were scraped with a scalpel under magnification to reveal the target paint layer. A small amount of this layer was then scraped onto a glass microscope slide, dispersing the pigments. The dispersed pigments were permanently embedded under a cover slip in Cargille Meltmount (Cargille Labs., Cedar Grove, NJ). The Meltmount used has a refractive index of 1.662. The prepared slides were then examined under the microscope with transmitted visible light using a polarizing filter at a magnification of 1000x with an oil immersion objective. The morphological and optical properties of the pigment particles was observed and compared to reference pigment samples.

Color Measurement Procedures

Color measurements were made using uncast samples that were selected under magnification. An effort was made to find a clean, unweathered areas for measurement whenever possible. All color measurements were made using a Minolta Chromameter CR-241 with a measurement area of 0.3mm for uncast samples and a measurement area of 1.8mm for paint swatches. This microscope has an internal, 360° pulsed xenon arc lamp and can measure color 42 with five color systems. The color systems used in this report are the CIE (Commission International de l'Eclairage) L*a*b* and the Munsell color system. Both systems use three values called tristimulus values to measure color that include hue (or color), the chroma (or saturation), and lightness to darkness. In the CIE L*a*b* color system L* represents lightness from 1 to 100 with 100 being the lightest, a* represents red to green with positive numbers being more red and negative numbers more green, and b* represents yellow to blue with positive numbers being more yellow and negative numbers more blue. This system was adjusted from the CIE Yxy system developed in 1931 to better represent the human eye's sensitivity to color. In the Munsell system, color measurements are given in the form of hue, value, and chroma with value representing lightness to darkness. CIE L*a*b* color measurement values are compared to each other using the Euclidian Distance formula or ΔE that calculates the difference between two color measurements.1 The ΔE formula equals the square root of the sum of the differences in the L* values squared, the differences in the a* values squared, and the differences in the b* values squared. Generally, a ΔE value of less than two represents colors that are difficult for the human eye to differentiate.

Commercial color matches were found using a database of CIE L*a*b* values of paints from Benjamin Moore, Sherwin William, Martin Senour, and Pittsburgh Paints that calculates ΔE values. The matches with the lowest ΔE values were compared to the uncast sample under magnification with a color-corrected light source to choose a final match.

Colorimetry Data

First-generation red-brown paint

| ΔE from average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR32 | 38.29 | 12.51 | 10.43 | 1.33 | |

| GR32 | 39.08 | 14.57 | 11.50 | 1.16 | |

| GR32 | 38.57 | 13.57 | 11.59 | 0.42 | best match to average |

| Average 38.65 | 13.55 | 11.17 |

| Commercial Paint Matches | ΔE from Average | ΔE from GR32 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM 2103-30 | 38.03 | 14.20 | 11.77 | 1.08 | 0.85 | |

| SW 2837 | 36.66 | 12.96 | 11.68 | 2.13 | 2.01 | |

| BM 2101-30 | 40.79 | 13.79 | 12.97 | 2.81 | 2.62 | |

| BM 2102-30 | 40.63 | 15.39 | 12.16 | 2.88 | 2.81 | |

| SW 1322 | 36.93 | 11.40 | 10.88 | 2.77 | 2.81 | |

| BM 2105-30 | 40.69 | 11.93 | 13.39 | 3.42 | 3.23 | |

| SW 2721 | 38.68 | 15.56 | 14.19 | 3.63 | 3.28 | |

| BM 2105-20 | 37.16 | 11.38 | 13.71 | 3.65 | 3.36 | |

| SW 2722 | 40.88 | 15.19 | 13.56 | 3.66 | 3.44 | |

| BM 2103-20 | 35.45 | 14.27 | 12.97 | 3.74 | 3.48 | |

| SW 1336 | 38.29 | 14.52 | 15.03 | 3.99 | 3.58 | |

| SW 1315 | 34.91 | 13.69 | 12.95 | 4.14 | 3.91 | best match by eye |

| SW 2715 | 36.38 | 16.86 | 11.75 | 4.05 | 3.96 | |

| BM HC 65 | 37.54 | 16.72 | 9.31 | 3.84 | 4.02 | |

| BM 2104-30 | 38.21 | 17.66 | 13.39 | 4.69 | 4.48 | |

| BM 2106-30 | 40.31 | 8.73 | 12.08 | 5.18 | 5.17 | |

| SW 2287 | 34.46 | 9.45 | 10.57 | 5.89 | 5.91 |

Second-generation dull yellow paint

| ΔE from average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR27 | 69.13 | 1.02 | 25.71 | 2.45 | best match to average |

| GR21 | 66.30 | 1.06 | 20.53 | 3.50 | |

| GR29 | 65.14 | 1.48 | 21.31 | 3.54 | |

| GR27 | 70.10 | 0.75 | 27.45 | 4.44 | |

| Average | 67.67 | 1.08 | 23.75 |

| Commercial Paint Matches | ΔE from average | ΔE from GR22 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW CW 308 | 68.18 | 0.80 | 29.19 | 5.47 | 2.59 | best match by eye |

| BM HC34 | 72.03 | 1.92 | 25.95 | 4.96 | 2.71 | |

| SW 2813 | 72.58 | -0.09 | 28.71 | 7.08 | 2.91 | |

| BM HC 38 | 69.02 | 2.00 | 24.73 | 1.91 | 3.18 | |

| BM 2161-40 | 70.25 | 6.07 | 26.07 | 6.08 | 5.50 | |

| BM 2162-40 | 66.03 | 4.62 | 28.72 | 6.32 | 5.76 | |

| BM HC 42 | 69.48 | 7.00 | 28.48 | 7.79 | 6.36 | |

| BM AC 5 | 69.25 | 3.39 | 19.76 | 4.88 | 8.17 | |

| BM HC 21 | 68.74 | 0.10 | 19.15 | 4.82 | 8.44 | |

| BM HC 43 | 62.84 | 3.86 | 24.04 | 5.58 | 8.60 | |

| SW 1145 | 65.49 | 0.78 | 19.05 | 5.19 | 9.58 | |

| MS W 1164 | 60.54 | 4.15 | 25.55 | 7.97 | 10.32 | |

| MS W 1060 | 59.20 | 2.91 | 25.43 | 8.82 | 11.29 | |

| BM HC 20 | 59.85 | 0.98 | 22.43 | 7.93 | 11.42 | |

| BM HC 37 | 59.24 | 3.99 | 29.95 | 10.86 | 11.61 | |

| MS W 1078 | 59.53 | 5.78 | 27.09 | 9.97 | 11.71 | |

| SW 1125 | 58.48 | 4.72 | 26.27 | 10.20 | 12.34 | |

| MS W 0390 | 84.13 | 1.52 | 28.60 | 17.17 | 14.10 | |

| SW 2824 | 53.16 | 4.90 | 26.46 | 15.25 | 17.47 |

Third-generation cream-colored paint

| GR30 | 76.63 | -0.40 | 12.74 | ||

| Commercial Paint Matches | ΔE from GR30 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM HC 80 | 76.88 | -0.04 | 13.35 | 0.75 | |

| SW 6149 | 76.97 | -0.94 | 13.15 | 0.76 | best match by eye |

| SW 2822 | 77.42 | -0.54 | 13.42 | 1.05 | |

| SW DCL 033 | 75.57 | -0.28 | 11.63 | 1.54 | |

| SW 2066 | 78.76 | 0.01 | 12.92 | 2.18 | |

| PP 414-4 | 75.79 | 0.17 | 14.70 | 2.21 | |

| MS W 1252 | 78.33 | -0.31 | 14.26 | 2.28 | |

| MS W 0330 | 76.25 | -2.67 | 13.14 | 2.34 | |

| SW 2065 | 74.44 | -0.28 | 13.79 | 2.43 | |

| BM AC 1 | 77.78 | -1.70 | 10.96 | 2.49 | |

| PP 415-4 | 74.74 | 1.19 | 13.04 | 2.49 | |

| SW 2073 | 77.90 | -0.10 | 10.54 | 2.56 | |

| SW 2058 | 74.35 | -0.03 | 13.93 | 2.60 | |

| BM HC 83 | 78.93 | -0.10 | 11.50 | 2.63 | |

| SW 2038 | 75.33 | -0.02 | 10.45 | 2.66 | |

| MS CW 707 | 90.40 | -1.60 | 10.60 | 13.99 | best match to fresh batch of lead white in oil |